Known worldwide as the father of the atomic bomb, and now, thanks to the title of this book, as American Prometheus, Robert Oppenheimer didn’t get enough credit for his breakthrough discoveries during his life. In the Cold-war era, Washington’s national security establishment saw him as a threat for being against the adoption of nuclear warfare and, although he wasn’t declared a spy in the 1954 trial, his reputation never fully recovered in the scientific community. Interested to know more? Get ready to hear what the life of one of the greatest scientific figures of the twentieth century looked like before this life-changing event.

Oppie did not lack anything in childhood

Robert Oppenheimer was born on April 22, 1904, in the decade when science initiated a second American revolution. Inventions such as the internal combustion engine, manned flight, and other technological innovations were about to change the lives of ordinary men and women significantly. Along with this revolution, many discoveries, such as radioactivity and Einstein’s theory of relativity, changed how people perceived space and time.

Not only did the moment when he came to the world determine his destiny, but also his origins. Oppenheimer came from a family of first and second-generation Jewish immigrants that moved from Germany to New York searching for a better life. Although he came to America without much money and no knowledge of English, Robert’s father, Julius, quickly thrived in the business world and became a full partner in the firm of Rothfeld, Stern & Company. By 1914, he was a prosperous businessman.

For a long time their only child, brought up primarily by a dedicated and overprotective mother, Robert did not lack anything in childhood. As a family friend Harold Cherniss recalled, “Robert was doted on by his parents. He had everything he wanted; you might say he was brought up in luxury.” However, despite the abundance, almost none of his friends perceived him as spoiled. “He was extremely generous with money and material things,” said Cherniss.

Robert’s parents encouraged their child to discover his passions and find enjoyable hobbies. As his cousin Babette Openeheimmer said, “He was given every opportunity to develop along the lines of his own inclinations and at his own rate of speed.” One of his passions was collecting minerals. When he was twelve, he corresponded with several well-known local geologists about the rock formations he studied in Central Park. One of the correspondents nominated him for membership in the New York Mineralogical Club and invited him to deliver a lecture to other members. Interestingly, the correspondent did not know Robert’s age, so when he stepped to the podium, rock collectors started laughing. Nevertheless, they soon discovered he, indeed, deserved to join their club and gave him a hearty round of applause after the lecture.

Oppenheimer’s education

In America, the Oppenheimer family belonged to the Ethical Culture Society, a uniquely American offshoot of Judaism that promoted social justice, rationalism, and a progressive band of humanitarianism. As the authors note, ‘’It was no accident that the young boy who would become known as the father of the atomic era was reared in a culture that valued independent inquiry, empirical exploration and the freethinking mind - in short, the values of science.’’ In September 1911, Robert enrolled in a unique private school run by Dr. Felix Adler, the Society’s leader and founder. According to the authors, this school had a powerful influence, not only in helping him acquire knowledge but also in shaping Robert’s psyche, both emotionally and intellectually. ‘’Throughout the formative years of his childhood and education,’’ they write, ‘’he was surrounded by men and women who thought of themselves as catalysts for a better world.’’ Although he excelled in all subjects, Robert was more eager to study science than languages and humanities. He was doing laboratory experiments as early as third grade, and, by the age of ten, he studied physics and chemistry. Everyone regarded him as gifted but also distant, and a bit difficult to get along with.

The difficulty with which he made deeper social connections continued to haunt him at Harvard, where he often felt lonely, melancholic, and depressed. Nevertheless, his intellect continued to thrive, and after a few months of taking various unrelated courses, including philosophy, French literature, history, and three chemistry courses, he decided to choose chemistry as his major, determined to graduate in three years. However, at the end of his freshman year, Robert regretted choosing chemistry over physics, and, therefore, asked the Physics Department for graduate standing, which would allow him to take upper-level physics courses, and they approved. However, Oppenheimer said that his approach to learning physics was not systematic - he mostly learned what he found interesting. Decades later, he admitted in an interview that he still felt panic when someone asked him a question related to fundamentals.

Oppenheimer’s to participate in the life of the community

“Beginning in late 1936, my interests began to change,’’ Oppenheimer said in a 1954 interrogation. ‘’I had had a continuing, smoldering fury about the treatment of Jews in Germany (...) I saw what the Depression was doing to my students. Often they could get no jobs, or jobs which were wholly inadequate. And through them, I began to understand how deeply political and economic events could affect men’s lives. I began to feel the need to participate more fully in the life of the community.”

Thanks to the Great Depression, many Americans reconsidered their political outlook, which was also true for Oppenheimer. He was drawn to the ideas of communism thanks to Marx's Capital which he read in German in only three days, and Jean Tatlock, a young communist he was dating then. ‘’It was Tatlock’s passionate nature to push Oppenheimer to move from theory to action,’’ the authors note. She and Oppenheimer organized fund-raisers for a variety of Spanish relief groups. Oppenheimer himself donated significant sums to the Spanish cause through the Communist Party and to assist German Jewish physicists to escape Nazi Germany. When he was asked about these donations at the trial, he stated that it did not occur to him that those contributions might be directed to evil purposes or those he did not intend. He said, ‘’I did not then regard Communists as dangerous; and some of their declared objectives seemed to me desirable.”

Some speculated that Oppenheimer’s political engagement was, above all, driven by his guilt ‘’about his gifts, about his inherited wealth, about the distance that separated him from others.” However, to his prosecutors in 1954, the motives of his engagement were not relevant - the fact that it existed was enough to spark their suspicion he was a spy and one of the main arguments for taking security clearance away from him.

The Manhattan Project

A month before war broke out in Europe, President Roosevelt got a letter signed by Albert Einstein (although physicist Leo Szilard actually wrote it), in which he warned the president “that extremely powerful bombs of a new type may be constructed,” and suggested that the German’s work on that bomb might already be in progress. Upon reading the letter, President Roosevelt established a ‘’Uranium Committee’’ led by physicist Lyman C. Briggs. However, there were no concrete results in creating the atomic bomb until the creation of the secret weapons lab led by Oppenheimer called the Manhattan Project. Oppenheimer was passionate about it and thought that constructing a bomb should be an urgent matter. He feared they were already losing a race against the Germans and that only the atomic bomb was powerful enough to remove Hitler from Germany.

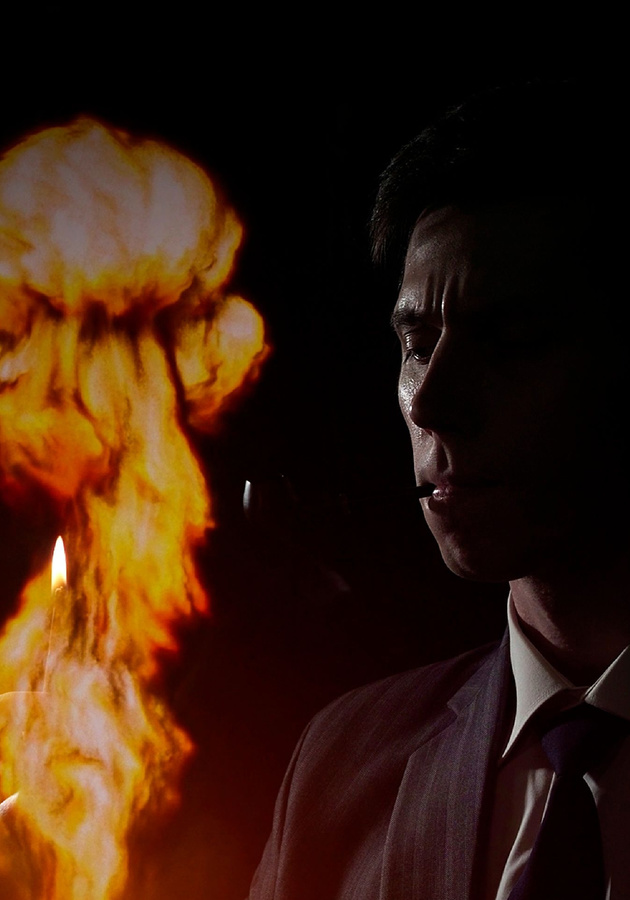

On July 16, 1945, a tremendous burst of light followed by ‘’the deep growling roar of explosion’’ on the test site Oppenheimer named Trinity announced the first testing of the bomb. Only a short time after the Trinity test, Oppenheimer found out that Army Air Force officers were picking targets. ‘’Those poor little people, those poor little people,’’ said Oppenheimer to his secretary, referring to the Japanese. So, it was obvious the bombs he brought into existence were going to be used, and he comforted himself that it was all for a good cause - not to encourage a post-war arms race with the Soviets. In the days prior to the bombing of Japanese cities, he was working hard to make sure that the bomb exploded efficiently and also recommended that the Russians be clearly informed of the possibility of bombing Japan. And although President Truman accepted his recommendation, he only casually mentioned to Stalin that they had a new unusually destructive weapon. ’’The Russian Premier showed no special interest,’’ wrote Truman in his memoir. ‘’All he said was that he was glad to hear it and hoped we would make ‘good use of it against the Japanese.’’’

Should the Super be built?

On August 29, 1949, an atomic bomb exploded at an isolated testing site in Kazakhstan. Several days later, high-ranking officials in the Truman administration got the news about the Soviet Union’s testing of the bomb. And soon after, the thing Oppenheimer was afraid of started happening - President Truman endorsed a Joint Chiefs proposal for increasing the production of nuclear weapons. And this was just the beginning. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) member Lewis Strauss (who was later the driving force in 1954 hearings) argued that America could gain military superiority over the Soviets only by developing a thermonuclear weapon - the Super.

Oppenheimer had always been skeptical about building a weapon thousands of times more destructive than an atomic bomb. He pinned his hopes on proving that its creation was technically unfeasible. “I am not sure the miserable thing will work,” he wrote to his friend James B. Conant, “nor that it can be gotten to a target except by ox-cart.” However, Oppenheimer’s concerns weren’t only those of a scientist - he was also disturbed by ethical implications because the hydrogen bomb would be too big for any known military target - it was simply a weapon that could wipe out entire cities. But, what if the Russians succeed in developing it? If that happened to be the case, Oppenheimer thought that America’s ‘’large stock of atomic bombs would be comparably effective to the use of a Super.”

In October 1949, the General Advisory Committee (GAC), composed of ‘’the most deeply informed and experienced atomic scientists in America,’’ whose which Oppenheimer was part of, wrote a report which listed the arguments against creating a hydrogen bomb. When three out of five AEC commissioners voted to endorse the GAC recommendations, Oppenheimer naively thought that the battle against Super had been won. However, Levis Strauss, Edward Teller, and other supporters of the bomb did not want to surrender that easily. And, on January 31, 1950, President Truman made a final decision pretty quickly, without a thorough evaluation of the consequences, when he heard that Russians could build a hydrogen bomb. “In that case,’’ he said, ‘’We have no choice. We’ll go ahead.”

Final Notes

Although lengthy and detailed, ‘’American Prometheus’’ is engaging and informative, and as such, makes the story of one of the greatest 20th-century scientists widely heard. It should be, in the words of a writer from ‘’The Boston Globe,’’ praised as ‘’an Everest among the mountains of books on the bomb project and Oppenheimer,’’ and ‘’an achievement not likely to be surpassed or equaled.”

12min Tip

If you haven’t already, watch the movie ‘’Oppenheimer’’ directed by Christopher Nolan to see the movie portrayal of the famous physicist.